Introduction

‘The Odyssey’ is such a timeless story not only for its terrifying monsters, rip-roaring action scenes, and wealth of information on Mediterranean geography and legends but also because it involves the irresistible plot line of a worthy hero trying desperately to get back to his city, his family, and his throne.

Thus, ‘The Odyssey’ is not only a great romantic, adventure epic, but it’s terribly realistic in its depiction of human nature and a brilliantly crafted narrative. Authors today could learn from how Homer lays out his plot and plays the characters off against each other for maximum reader involvement.

Of course, it was composed almost three thousand years ago and our sensibilities have changed rather drastically in those centuries. So, the readerhas to work a bit at putting himself/herself in the ancient mindset and understanding it, especially when his/her copy of ‘The Odyssey’ is translated as poetry.

But when he/she does make that effort, he/she will find it starts coming easier and easier, and it ends up seeming not so ancient or foreign after all. It eventually sucks him/her right into the tale.

This ebook includes the brief passage in Book IX of Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, in which after nine days of storms Odysseus finds himself beached on an unknown island. He sends scouts to contact the inhabitants, a gentle race who live on the ‘flowery lotus fruit’. Some of Odysseus’ crew taste the fruit, after which they lose all desire to continue their voyage: ‘all they now wanted was to stay where they were with the Lotus-eaters, to browse on the lotus, and to forget all thoughts of return’. Odysseus resists the temptation to taste the lotus; instead, he drags his crew forcibly back to the ship and sets sail as quickly as possible, ‘for fear that others of them might eat the lotus and think no more of home’.

Legends of the land of the lotus-eaters persisted in the ancient world. Herodotus, in his Histories, records a tradition locating it near the coast of Africa: perhaps near Libya, perhaps the island of Djerba off present-day Tunisia. He speculates, too, about its botanical identity: some believed it to be a sweet and heady fruit like the date, and others a wine made from such a fruit. More recently, it has been suggested that its flower might have been that of the Egyptian blue water-lily (Nymphaea caerulea), which is now known to have mild psychoactive and sedative properties. But the appeal of the story has always been more mythical than literal. Odysseus was the archetypal man on a mission: the central theme of his story, and the core of his character, is his determination to resist all distractions and temptations, remaining focused on his prime imperative. Just as he was obliged to stop his ears to the song of the sirens, he could not allow himself to taste the lotus fruit. Across the subsequent centuries his self-command, and the conviction with which he lashes his unwilling crew to the oars, has exemplified the ideal of leadership.

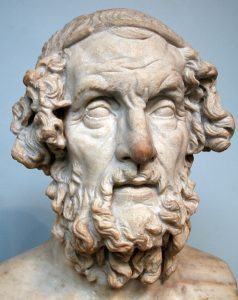

Homer

In order to understand the evolution of the Hellenic civilization it is necessary to go back to the first period of its history, the Homeric Age which extended from approximately 1200 to 800 BC. It was the that the Greek nation was formed and the foundations laid for many of the social and political developments of subsequent centuries. Not all of the glory that was Greece can be traced to the Homeric Age, but it is nonetheless true that several of the most typical institutions and attributes of the Greeks in their prime were modifications of forms which had survived from the earliest days.

Little is known about the author called “Homer”—so little that there is speculation he never existed. One theory posits that he was a blind man who lived sometime during the 8th century BCE and that the Greeks considered him to be their greatest poet. Another theory holds that the name “Homer” merely stands in for many authors who expanded on the story of ‘The Odyssey’ over generations. One thing that contemporary historians can agree on is that, even if one person did indeed write ‘The Odyssey’ (and its companion, ‘The Iliad’), it had its genesis in a long tradition of oral storytelling that wasn’t written down for centuries. These stories would be handed down through generations, and each storyteller would add new details or fine-tune the content. Who exactly Homer was remains one of the great literary mysteries yet to be solved—a mystery that scholars have named “the Homeric Question.”

Despite the mystery around his origins and life, Homer has influenced storytelling ever since his works came into being. ‘The Odyssey’ established the model of the epic quest and has inspired countless retellings. This epic also provides a rare poetic glimpse at life in ancient Greek society. Furthermore, Homer employed a variety of literary devices, such as metaphors, that have influenced authors for millennia.

CONTEXT ELEMENT

By 1200 BC the Greeks had occupied most of the northern sections of the peninsula and a few scattered locations along the coast. At first, they filtered in slowly, bringing their herds and flocks with them and settling in the more sparsely populated areas. Many of these early immigrants seem to have belonged to the group which later came to be known as Ionians. Another division the Achaeans pushed further south, conquered Mycenae and Troy, and ultimately gained dominion over Crete. Soon after 1200 the great Dorian invasions began and reached their climax about two centuries later. Some of the Dorians settled in central Greece, but most of them took to the sea, conquering the eastern sections of the Peloponnesus and the southern islands of the Aegean. About 1000 BC they captured Knossos, the chief center of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete.

Whether Achaeans, Ionians, or Dorians, all of the Greeks in the Homeric Age had essentially the same culture, which was comparatively primitive. Not until the very last century of the period was there any general knowledge of writing. We must therefore envisage the Homeric Greeks as a preliterate people during the greater part of their history, with intellectual accomplishments that extended no farther than development of folk songs, ballads, and short epics sung and embellished by bards as they wandered from one village to another. A large part of this material was finally woven into a great epic cycle by one or more poets and put into written form in the ninth century BC. Though not all of the poems of this cycle have come down to us, the two most important, ‘the Iliad’ and ‘the Odyssey’, provide us with our richest store of information about the ideals and customs of the Homeric Age.

The political institutions of the Homeric Greeks were exceedingly primitive. Each little community of villages was independent of external control, but political authority was so tenuous that it would not be too much to say that the state scarcely existed at all. The king could not make or enforce laws or administer justice. He received no remuneration of any kind, but had to cultivate his farm for a living the same as any other citizen. Practically his only functions were military and priestly. He commanded the army in time of war and offered sacrifices to keep the gods on the good side of the community. Although each little group of villages had its council of nobles and assembly of warriors, neither of these bodies had any definite membership or status as an organ of government. The duties of the former were to advise and assist the king and prevent him from usurping despotic powers. The functions of the latter were to ratify declarations of war and assent to the conclusion of peace. Almost without exception custom took the place of law, and the administration of justice was private. Even willful murder was punishable only by the family of the victim. While it is true that disputes were sometimes submitted to the king for settlement, he acted in such cases merely as an arbitrator, not as a judge. As a matter of fact, the political consciousness of the Greeks of this time was so poorly developed that they had no conception of government as an indispensable agency for the preservation of social order. When Odysseus, king of Ithaca, was absent for twenty years, no regent was appointed in his place, and no session of the council or assembly was held. No one seemed to think that the complete suspension of government, even for so long a time, was a matter of any critical importance.

As is commonly known, the deities of the Homeric religion were merely human beings writ large. It was really necessary that this should be so if the Greek was to feel at home in the world over which they ruled. Remote, omnipotent beings like the gods of most Oriental religions would have inspired fear rather than a sense of security. What the Greek wanted was not necessarily gods of great power, but deities he could bargain with on equal terms. Consequently he endowed his gods with attributes similar to his own— with human bodies and human weaknesses and wants. He imagined the great company of divinities as frequently quarreling with one another, needing food and sleep, mingling freely with men, and even procreating children occasionally by mortal women. They differed from men only in the fact that they subsisted on ambrosia and nectar, which made them immortal. They dwelt not in the sky or in the stars but on the summit of Mount Olympus, a peak in northern Greece with an altitude of about 10,000 feet.

The religion was thoroughly polytheistic, and no one deity was elevated very high above any of the others. Zeus, the sky god and wielder of the thunderbolt, who was sometimes referred to as the father of the gods and of men, frequently received less attention than did Poseidon, the sea god, Aphrodite, goddess of love, or Athena, the goddess of war and patroness of handicrafts. Since the Greeks had no Satan, their religion cannot be described as dualistic. Nearly all of the deities were capable of malevolence as well as good, for they sometimes deceived men and caused them to commit wrongs. The nearest approach to a god of evil was Hades, who presided over the nether world. Although he is referred to in the Homeric poems as “implacable and unyielding” and the most hateful of gods to mortals, he was never assumed to have played an active role in affairs on earth. He was not considered as the source of pestilence, earthquake, or famine. He did not tempt men or work to defeat the benevolent designs of other gods. In short, he was really not regarded as anything more than the guardian of the realm of the dead.

The Greeks of the Homeric Age were almost completely indifferent to what happened to them after death. Not only did they bestow no care upon the bodies of the dead, but they frequently cremated them. They did assume, however, that the shades or ghosts of men survived for a time after the death of their bodies. All, with a few exceptions, went to the same abode—to the murky realm of Hades situated beneath the earth. This was neither a paradise nor a hell: no one was rewarded for his good deeds, and no one was punished for his sins. Each of the shades appeared to continue the same kind of life its human embodiment had lived on earth. The Homeric poems make casual mention of two other realms, the Elysian Plain and the realm of Tartarus, which seem at first glance to contradict the idea of no rewards and punishments in the hereafter. But the few individuals who enjoyed the ease and comfort of the Elysian Plain had done nothing to deserve such blessings; they were simply persons whom the gods had chosen to favor. The realm of Tartarus was not really an abode of the dead but a place of imprisonment for rebellious deities.

Worship in the Homeric religion consisted primarily of sacrifice. The offerings were made, however, not as an atonement for sin, but merely in order to please the gods and induce them to grant favors. In other words, religious practice was external and mechanical and not far removed from magic. Reverence, humility, and purity of heart were not essentials in it. The worshiper had only to carry out his part of the bargain by making the proper sacrifice, and the gods would fulfill theirs. For a religion such as this no elaborate institutions were required. Even a professional priesthood was unnecessary. Since there were no mysteries and no sacraments, one man could perform the simple rites about as well as another. As a general rule, each head of a family implored the favor of the gods for his own household, and the king performed the same function for the community at large. Although it is true that seers or prophets were frequently consulted because of the belief that they were directly inspired by the gods and could therefore foretell the future, these were not of a priestly class. Furthermore, the Homeric religion included no cult or sacred relics, no holy days, and no system of temple worship. The Greek temple was not a church or place of religious assemblage, and no ceremonies were performed within it. Instead it was a shrine which the god might visit occasionally and use as a temporary house.

As intimated already, the morality of the Greeks in the Homeric period had only the vaguest connection with their religion. While it is true that the gods were generally disposed to support the right, they did not consider it their duty to combat evil and make righteousness prevail. In meting out rewards to men, they appear to have been influenced more by their own whims and by gratitude for sacrifices offered than by any consideration for moral character. The only crime they punished was perjury, and that none too consistently. The conclusion seems justified, then, that Homeric morality rested upon no basis of supernatural sanctions. Perhaps its true foundation was military. Nearly all the virtues extolled in the epics were those which would make the individual a better soldier— bravery, self-control, patriotism, wisdom (in the sense of cunning), love of one’s friends, and hatred of one’s enemies. There was no conception of sin in the Christian sense of wrongful acts to be repented of or atoned for.

At the end of the Homeric Age the Greek was already well started along the road of social ideals that he was destined to follow in later centuries. He was an optimist, convinced that life was worth living for its own sake, and he could see no reason for looking forward to death as a glad release. He was an egoist, striving for the fulfillment of self. As a consequence, he rejected mortification of the flesh and all forms of denial which would imply the frustration of life. He could see no merit in humility or in turning the other cheek. He was a humanist, who worshiped the finite and the natural rather than the otherworldly or sublime. For this reason, he refused to invest his gods with awe-inspiring qualities, or to invent any conception of man as a depraved and sinful creature. Finally, he was devoted to liberty in an even more extreme form than most of his descendants in the classical period were willing to accept.

‘The Odyssey’ was written, as mentioned before, around 700 BC during the Archaic period (750 – 550 BC). This was a time of great economic and social change in Greek history due to massive migration that led to the development of new city-states (called the polis) as well as laws to govern them. Citizenship and political rights give a good indication of women’s roles in Greek society.

Upon marriage, woman became the legal wards of their husbands, as they previously had been of their fathers while still unmarried. It was common for a father to sell his young daughter into marriage and the young women had no say in her preference of her suitors. This was done while the girl was in her young teens while the groom was ten to fifteen years older. As the father, or guardian, gave the young girl away he would repeat the phrase that expressed the primary aim of marriage: “I give you this woman for the plowing [procreation] of legitimate children”. The woman’s role was primarily in the home. Households thus depended on women, whose wok permitted the family to economically self-reliant and the male citizens to participate in the public life of the “polis” (city).

The litterary work

‘The Odyssey’ picks up the story of Odysseus 10 years into his journey home from the Trojan War, which itself had lasted 10 years. As with the Iliad, the poem is divided into 24 books. The episode of Odysseus and the Lotus Eaters can be found in the Book XI.

The story opens with Odysseus being held captive by the goddess Calypso on a remote island. Back in his home city, Ithaca, his wife, Penelope, is being besieged by suitors, who have moved into her home, taking advantage of the ancient Greek custom of hospitality. Telemachus, son of Odysseus and Penelope, must watch the suitors take over their house, waiting for Penelope to choose a new husband. All—except Penelope—assume Odysseus is dead after his 20-year absence.

Athena, the goddess of war, has been watching over Odysseus since the Trojan War.

She feels protective toward him and asks Zeus to help her free Odysseus from Calypso’s island. Zeus sends his son Hermes to aid Odysseus in his escape. At the same time, Athena goes to Ithaca to offer help to Penelope and Telemachus. She advises the son to leave Ithaca to find information on the whereabouts of his father. The suitors take note of the newfound courage and authority that Telemachus displays, and they conspire to murder him when he returns to Ithaca. On his visit to King Menelaus on the island of Sparta, Telemachus learns that Odysseus is alive.

Hermes helps free Odysseus, who sails to the land of the Phaeacians. Exhausted, he collapses on the shore, where the princess Nausicaa discovers him. She leads him to the king, Alcinous, and his queen, Arete. There Odysseus tells them the story of his travels thus far. He and his men had run into a number of trials on their way home to Ithaca. They nearly lost themselves and their memories in the land of the Lotus-eaters and then incurred the wrath of Poseidon by blinding his son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. Odysseus and his crew were given a pouch full of sailing winds by Aeolus, but curiosity got the best of his men and they accidentally released the winds, which blew them off course and far from home. They encountered cannibals and witches, Odysseus visited the Land of the Dead, they avoided the lure of the deadly songs of the Sirens, and they escaped from numerous monsters. Odysseus lost his men one by one, and the rest were wiped out when they ate the cattle of Helios, which the blind prophet Tiresias had warned Odysseus about. They were punished by a single lightning bolt sent down by Zeus, which destroyed Odysseus’s ship. He washed ashore on the island of Ogygia, where Calypso held him captive for seven long years.

Hearing the stories of Odysseus’s journey, King Alcinous comes to his aid by providing him with a ship. Athena also helps Odysseus once again, forewarning him of the chaos at home in Ithaca and informing him that the worst is yet to come. She disguises Odysseus as a beggar and tells him to stop in at the farm of his old friend, the swineherd Eumaeus, before he goes to his house. She also orchestrates the reunion between Odysseus and Telemachus, whom she has advised to come home. Telemachus relates to Odysseus the behavior of the suitors, and they plot the mass murder of the suitors to restore honor to their home.

A few characters begin to recognize Odysseus through his disguise—among them his childhood dog Argos and his childhood nurse Eurycleia. However, his wife, Penelope, does not recognize him. When the suitors encounter Odysseus disguised as a beggar, they are cruel to him, taunting him and making him fight another beggar. But Odysseus is able to practice restraint and bide his time until his plan can be enacted. Penelope declares that she will hold a contest to choose her next husband—whoever can master Odysseus’s bow to shoot down a row of axes will win. When the contest begins, none of the suitors can so much as string the bow.

The still-disguised Odysseus volunteers to undertake the challenge, to the chagrin of the suitors, but Penelope allows him to try. He strings the bow and shoots through the axes easily. The suitors are shocked, and Odysseus, taking advantage of their confusion, begins to kill them and the serving women who helped them. Athena once again offers aid, and Telemachus and loyal servants join in as well. Finally, Odysseus and Penelope are reunited, but not without a final test on the part of Penelope to ensure Odysseus’s identity. However, they cannot live happily ever after just yet—the families of the slain suitors want revenge. The gods finally intervene, with both Athena and Zeus commanding peace. Odysseus’s final journey is to see his father and then to offer a sacrifice to Poseidon, so that the god will leave him and his family in peace.

The literary genre

An epic poem is a long narrative poem written in a grand or lofty style that recounts the adventures of heroes; expresses cultural values; and has cultural, national, or religious significance. The word epic is actually derived from the Greek epos, which means “lines” or “verses” and thus underscores the poetic nature of the genre. In ancient Greece epics were recited by bards, or singers, at special occasions. They were transmitted orally for centuries before they were written down. ‘The Odyssey’, which drew on this oral tradition, is one of the oldest epics ever recorded in writing.

Epic poems have several characteristics. ‘The Odyssey’ and ‘The Iliad’ helped establish several conventions of the epic. These conventions include focus on a hero of cultural or national importance who has many adventures, a wide geographic scope with many settings, battles requiring heroic deeds, possibly an extended journey, and the involvement of supernatural beings such as gods. All of these elements are present in ‘The Odyssey’.

Other conventions of literary epics involve how the story is told—and these conventions are generally attributed to Homer. Epic poems typically begin with an invocation of the Muse. The Muses were the nine Greek goddesses of the various arts and included Calliope, the goddess of epic poetry. The invocation is the poet’s request for divine inspiration. Epics begin in media res, or in the middle of the action, rather than at the beginning. Events leading to that point are related in flashbacks. Homeric epics employ epithets, which are phrases associated with particular characters or phenomena that are often presented when that character or phenomena is referred to anew. Thus, in The Odyssey Athena is often called “sparkling-eyed Athena” or “the bright-eyed goddess,” and the goddess Dawn is referred to as “young Dawn with her rose-red fingers.” Among mortals Odysseus is often “godlike,” “great-hearted,” and “much-enduring.” Telemachus is frequently called “clear-sighted,” “clear-headed,” and “pensive,” and Menelaus is “the red-haired king.” These epithets are, in fact, units of meaning fashioned to fit the meter of the poem that are variously used depending on the metrical needs of a given line of poetry. Finally, epics are traditionally divided into 24 sections, called books.

Later epic poets consciously followed these conventions to some extent. Both the Roman poet Virgil in the Aeneid and the English poet John Milton in Paradise Lost invoke the Muse and begin in media res. Their epics have 12 rather than 24 books, but that there are exactly half as many divisions as in Homer’s works clearly shows the influence of the Greek epics.

Its European, or international dimension

An everyman’s tale and a romance, ‘the Odyssey’ is filled with adventure, longing and temptation, the struggle between good and evil, and hard-won triumph. It is an enduring classic because its hero, Odysseus, and his story, though centuries old, are remarkably human and continue to grip the contemporary imagination.

‘The Odyssey’, Homer’s second epic, is the story of the attempt of one Greek soldier,

Odysseus, to get home after the Trojan War. All epic poems in the Western world owe something to the basic patterns established by these two stories.

‘The Odyssey’ is the model for the epic of the long journey. The theme of the journey has been basic in Western literature—it is found in fairy tales, in such novels as ‘The Incredible Journey’, ‘Moby-Dick’, and ‘The Hobbit’, and in such movies as ‘The Wizard of Oz’ and ‘Star Wars’. Thus, the ‘Odyssey’ has been the more widely read of Homer’s two great stories.

More specifically, the rich variety of mythical narratives in the Odyssey (especially his wanderings through a world of wonder and mystery in Books 9 to 12) has meant that the cultural history of the poem is astonishingly large, whether in literature or art or film. Whole monographs have been written on the reception of Odysseus in later periods. When one bears in mind that Odysseus’s name at Rome, Ulysses, is often used by artists and writers, as it was by James Joyce, then we get a sense of how dominant a figure he is in western cultural history.

Creative re-tellings of ‘the Odyssey’ in a modern context include films such as 2001: ‘A Space Odyssey’, ‘Paris’, ‘Texas’, and ‘O Brother Where Art Thou?’ Likewise the theme of the returning war veteran has Homeric overtones in films like ‘The Manchurian Candidate’, ‘The Deer Hunter’ and ‘In the Valley of Elah’.

Odysseus, moreover, probably influenced the early comic book superhero Batman in the late 1930s and 40s, just as Greek demigods, such as Heracles and Achilles, help to inform the extra-terrestrial background of Superman. As a human bat, Batman uses disguise to good effect, as Odysseus does, and he thrives on conducting his challenges in the darkness of night.

But the last word on the subject of Odysseus and his adventures should go to Bob Dylan, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. Dylan wrote a lecture in honour of his Nobel victory, focused on some of the literature that influenced and affected him. One such work was the Odyssey, and with echoes of Constantine Cavafy’s magnificent poem Ithaca, Dylan reflects on Odysseus’ adventures and their immediacy as a lived experience:

“In a lot of ways, some of these same things have happened to you. You too have had drugs dropped into your wine. You too have shared a bed with the wrong woman. You too have been spellbound by magical voices, sweet voices with strange melodies. You too have come so far and have been so far blown back. And you’ve had close calls as well. You have angered people you should not have. And you too have rambled this country all around. And you’ve also felt that ill wind, the one that blows you no good. And that’s still not all of it.”

Major issues/problems of the time addressed

‘The Odyssey’ is narrated from a third-person point of view by a narrator who has invoked the divine authority of the Muse, which allows the narrator to know everything and understand all the characters’ thoughts and feelings. The poem begins “Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns…” establishing a point of view that is all-seeing, all-knowing, and close to the divine. The poem shifts between narrative passages and direct speech, sometimes quoting one character within another character’s speech.

The point of view shifts entirely to Odysseus during books 9-12, when he tells about his adventures at sea before landing on Calypso’s island, making the poem feel like a first-person account for a lengthy stretch of narrative. In these sections the narrator interrupts Odysseus a few times to remind the audience where they are and who is talking, but mostly Odysseus’s narrative is continuous and first-person. This portion of the poem functions as a story-within-a-story as Odysseus gives a detailed and vivid description of his adventures since leaving Troy on what he hoped would be a quick journey home. As most of the action of the poem has already taken place by the time we first see Odysseus on Calypso’s island, this shift to the first person makes those events more gripping and immediate than if they were told in the third person by the narrator.

The various perspectives through which the poem is narrated provide different voices for the moral issues at the heart of ‘The Odyssey’. Odysseus encounters many “hosts” on his journeys, and most of them do not act in accordance with the customs of Greek hospitality. Because we witness much of the action through Odysseus’s point of view, we understand the contrast between his expectations of hospitality versus the reality of his experiences. The gods offer another perspective on the expectations of hospitality. Athena, for example, fights alongside Odysseus and Telemachus to slaughter the suitors as punishment for their abuse of the guest-host relationship. While the gods are rarely the main focus of scenes within the poem, we understand their point of view on the importance of Greek values through their speech.

Odyssey

Themes

Hubris

Many characters in ‘The Odyssey’ display hubris, the arrogance of overweening pride. They generally suffer for it. Even Odysseus, who is in the end reunited with the devoted Penelope and his loving son, Telemachus, and who is reconciled with father Laertes, suffers for a decade before reaching that point. While it’s true that suffering is sometimes in the arms of the lovely Circe or the beautiful Calypso, his seven years with her reduced him to a despondent, tearful man—hardly the picture of someone content with giving in to temptation. The arrogant Antinous is the first to die, and the arrogant Polyphemus, convinced that mere humans cannot harm him, is tricked and punished with blindness.

Temptation

Temptation befalls many of the characters in ‘The Odyssey’, and the outcome is usually a frustrating setback. Odysseus and his men succumb to temptation on numerous occasions, usually with disastrous consequences. Odysseus’s men fall prey to the Lotus-eaters and barely escape with their memories intact. They open the pouch of winds out of curiosity, only to find themselves blown far from the home they had almost reached. When they encounter the songs of the Sirens, they protect themselves from temptation by plugging their ears with beeswax but must lash Odysseus to the mast because he is too tempted by the alluring song to apply this countermeasure. Perhaps their greatest fall to temptation, however, is eating the cattle of Helios, after repeatedly being warned not to. Zeus is so angry that he slaughters every last one of them.

Homecoming

The central drive of the epic is Odysseus’s desire to return home, to reach the love of his family and the comfort of his palace. With home is tied the idea of loyalty and fidelity, with Penelope, Telemachus, and the loyal servants being the chief representatives. Penelope endures years of importuning by the obnoxious suitors, demonstrating her worth by keeping them at bay through stratagems worthy of her cunning husband’s mind. Telemachus, despite his father’s two-decade absence, feels the proper fidelity and devotion of a son, an indication of his virtue. While Odysseus must first disguise himself upon reaching Ithaca—as he does so often throughout his adventures—home represents the place where he can finally be his true self: master strategist, skilled warrior, loving husband, guiding father, and dutiful son.

The stories of Menelaus and Agamemnon, related by Menelaus to Telemachus, provide interesting contrasts. Menelaus must also undergo trials and effectively do penance to the gods in order to reach home peacefully. Agamemnon, however, came back to the danger of an unfaithful wife and her murderous lover. The success of a homecoming depends on the merits of those one comes home to.

Hospitality

Modern readers tend to be surprised at the overwhelming emphasis placed on hospitality in ‘The Odyssey’. It seems to dictate not only social interactions among mortals but also treatment by the gods. Hospitality is how characters assess one another’s moral code, and it’s how they stay safe in a world where people are constantly venturing into foreign and unknown lands. Travelers in ancient Greece (and there were many) had to rely upon the kindness of strangers for food, shelter, and warmth. To invest in being a hospitable host meant that it was more likely that the host, too, would encounter a warm welcome should he or she ever be lost or in need. Hosts usually enjoyed having strangers visit—strangers who brought tales of strange lands and stories of adventures to entertain them with.

Odysseus encounters a range of hospitality throughout the epic—from the helpfulness of the Phaeacians to the murderousness of the Cyclops. Even Odysseus must return to his own home to punish the suitors who abused the rules of hospitality that custom dictated must be extended to them.

Deception

Deception touches nearly every major character in ‘The Odyssey’. Athena is nearly always in disguise when she advises Odysseus, who is often in disguise as well or is careful about how and when he reveals his true identity. It’s no coincidence that it is often Athena who masterminds Odysseus’s disguises, altering his appearance to make him seem stronger or weaker as befits her plans.

Illusion and trickery are traits that both Odysseus and Athena admire, and not just when it comes to physical appearances. Odysseus deploys deception when he cannot rely on strength alone, such as when he tricks Polyphemus into believing that his name is “Nobody” in order to deter his neighbors from coming to his aid. Penelope and Telemachus both dissemble as well; being cagey is apparently a useful survival mechanism.

Fate

Fate seems to be the strongest force in shaping mortals’ lives. The gods determine mortals’ fate, though human action has weight. Sometimes it seems as though the gods decide the bigger picture but leave mortals power to make specific choices. No one counseled Odysseus on how to handle the problem of Polyphemus. Anchinous and Arete chose to offer Odysseus hospitality. Tiresias warns Odysseus that his men should not eat the cattle of Helios, but he didn’t say that they had no choice in the matter. He only told them they would suffer dire consequences if they did. That he was right did not mean those consequences were inevitable—only that fate was unavoidable if they made certain choices.

Justice

Adherence to customs decreed by the gods’ rules much of mortal behavior in ‘The Odyssey’. Disregarding those customs can get a mortal swiftly punished, both by other mortals and by the gods. The gods feel justified in punishing mortals any time they feel disrespected or if a mortal has reached too far—for example, become too arrogant. Zeus is the ultimate dispenser of justice, or at least the ultimate rule-setter. Even a powerful god such as Poseidon must submit to his decisions.

Vengeance

Vengeance is another major theme of ‘The Odyssey’, found in the plot of Poseidon’s revenge on Odysseus, the story of Orestes and Electra’s revenge on Aegisthus and Clytemnestra for the murder of their father Agamemnon, and on Telemachus and Odysseus’s destruction of the suitors and the maidservants. In each case the avenging party punishes a violation of the natural order. To Poseidon, Odysseus showed him too little devotion, albeit the warrior was unaware of Polyphemus’s relation to Poseidon. Aegisthus and Clytemnestra clearly violated the trust that Agamemnon had placed in them, and violated the loyalty due to him as a ruler and as a husband. The suitors abandoned the proper behavior due from a guest, and the servants showed disloyalty. Vengeance is implacable and usually thorough. Only because Poseidon was countermanded by Zeus does Odysseus survive.

The gallery of characters

- Odysseus: The protagonist of ‘The Odyssey’, Odysseus is a classic epic hero. He is by turns cunning, deceitful, clever, prudent, wise, courageous, and impulsive. A distinguishing characteristic about him is that his mental skills are just as strong as his physical strengths, and this ability helps him escape some dangerous situations. Odysseus has weaknesses—a tendency to give in to temptation, for example—as well as strengths. Odysseus is on the long journey home from taking part in the Achaeans’ victory in the Trojan War, depicted in The Iliad. Glory and honor have been the most important things in his life up to this point, but now he yearns for his family and home.

- Telemachus: Telemachus is Odysseus’s son, and the two have not seen each other in 20 years, since Telemachus was a baby. In many ways, Telemachus’s journey as a character is as important as his father’s. Still growing up when the story begins, he must learn to take charge and find the courage to dispel the hoards of suitors who have besieged his home and his mother. Under the guidance of Athena (who also guides his father), he matures and gains confidence. His assertiveness upsets the suitors, who have only seen him as a little boy up until the time covered by the narrative. By the end of the epic, he is confident and cunning, like his parents, practicing prudence and restraint in order to defeat the suitors.

- Penelope: Penelope is the wife of Odysseus and the mother of Telemachus. When The Odyssey opens, she has been waiting for Odysseus to return for 20 years. In that time her home has become besieged by suitors who take advantage of her hospitality and wait for her to choose one of them as a husband. Yet a part of her still hopes that Odysseus will return, and she uses ploys as deceptive as her husband’s to fool the suitors into waiting longer and longer. She does this by claiming she will choose a husband as soon as she finishes weaving a shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes. What the suitors don’t know is that by night she undoes the day’s work, which means that the shroud will never be finished. Penelope proves herself to be just as shrewd and smart as her husband throughout the epic.

- Lotus-Eaters: In Greek mythology, the lotus-eaters (Greek: λωτοφάγοι, translit. lōtophágoi) were a race of people living on an island dominated by the lotus tree, a plant whose botanical identity (if based on a real plant at all) is uncertain. The lotus fruits and flowers were the primary food of the island and were a narcotic, causing the inhabitants to sleep in peaceful apathy. After they ate the lotus, they would forget their home and loved ones, and only long to stay with their fellow lotus-eaters. Those who ate the plant never cared to report, nor return. Figuratively, ‘lotus-eater’ denotes “a person who spends their time indulging in pleasure and luxury rather than dealing with practical concerns”.

The location

Herodotus, in the fifth century BC, was sure that the lotus-eaters still existed in his day, in coastal Libya:

“A promontory jutting out into the sea from the country of the Gindanes is inhabited by the lotus-eaters, who live entirely on the fruit of the lotus-tree. The lotus fruit is about the size of the lentisk berry and in sweetness resembles the date. The lotus-eaters even succeed in obtaining from it a sort of wine.”

Polybius identifies the land of the lotus-eaters as the island of Djerba (ancient Meninx), off the coast of Tunisia. Later this identification is supported by Strabo.

Iconography in the ebook

To illustrate ‘Odysseys’ ebook, we have privileged contemporary painters of the work, namely:

- Louis Stanislas d’Arcy Delarochette (1731-1802) was a cartographer, possibly engraver, active in England but presumably of French origin and perhaps nationality.

- Jacob Jordaens (19 May 1593 – 18 October 1678) was a Flemish painter, draughtsman and tapestry designer known for his history paintings, genre scenes and portraits. After Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, he was the leading Flemish Baroque painter of his day.

- Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, known as the Goethe Tischbein (15 February 1751 in Haina – 26 February 1829 in Eutin), was a German painter from the Tischbein family of artists. He began his artistic studies with his uncle, Johann Jacob Tischbein in Hamburg. From 1772 to 1773, he travelled in Holland, studying the Old Masters. After 1777, he established himself as a portrait painter in Berlin.

- Joseph Wright ARA, styled Joseph Wright of Derby, was an English landscape and portrait painter. He has been acclaimed as “the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution”.

- Antoine-François Callet (1741–1823, Paris), generally known as Antoine Callet, was a French painter of portraits and allegorical works, who acted as official portraitist to Louis XVI. He won the grand prix de Rome in 1764 with ‘Cléobis et Biton conduisent le char de leur mère au temple de Junon’ (‘Kleobis and Biton dragging their mother’s cart to the temple of Juno’).

- Abraham van Diepenbeeck (9 May 1596 (baptised) – between May and September 1675) was Dutch painter of the Flemish School. After having received a classical education, he became a pupil and assistant of Peter Paul Rubens. He handled mythological and historical subjects, as well as portraits.

- Franz Josef Karl Edler von Matsch (16 September 1861, Vienna — 5 October 1942, Vienna), also known as Franz Matsch, was an Austrian painter and sculptor in the Jugendstil style. Along with Gustav and Ernst Klimt, he was a member of the Maler-Companie.

- Daniel van Heil or Daniël van Heil (Brussels, 1604 – Brussels, 1664), was a Flemish Baroque landscape painter. He specialised in three types of landscapes: scenes with fire, landscapes with ruins and winter landscapes.

- Claude Lorrain (1600 – 23 November 1682) was a French painter, draughtsman and etcher of the Baroque era. He spent most of his life in Italy, and is one of the earliest important artists, apart from his contemporaries in Dutch Golden Age painting, to concentrate on landscape painting. His landscapes are usually turned into the more prestigious genre of history paintings by the addition of a few small figures, typically representing a scene from the Bible or classical mythology.

- Theodoor van Thulden (1606–12 July 1669) was a painter, draughtsman and engraver from ‘s-Hertogenbosch. He is mainly known for his altarpieces, mythological subjects, allegorical works and portraits. He was active in Antwerp, where he had trained, as well as in Paris and his native Hertogenbosch.

- Joseph Mallord William Turner RA (23 April 1775 – 19 December 1851), known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colourisations, imaginative landscapes and turbulent, often violent marine paintings. He left behind more than 550 oil paintings, 2,000 watercolours, and 30,000 works on paper. He was championed by the leading English art critic John Ruskin from 1840, and is today regarded as having elevated landscape painting to an eminence rivalling history painting.

- Henryk Hektor Siemiradzki (24 October 1843 – 23 August 1902) was a Polish painter based in Rome, best remembered for his monumental academic art. He was particularly known for his depictions of scenes from the ancient Greek-Roman world and the New Testament, owned by many national galleries of Europe. Many of his paintings depict scenes from antiquity, often the sunlit pastoral scenes or compositions presenting the lives of early Christians. He also painted biblical and historical scenes, landscapes, and portraits. His best-known works include monumental curtains for the Lviv (Lwów) Theatre of Opera and for the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków.

- Edouard Manet (23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, and a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

- William Heath Robinson (31 May 1872 – 13 September 1944) was an English cartoonist, illustrator and artist, best known for drawings of whimsically elaborate machines to achieve simple objectives.

- William Edward Frank Britten (1848 – 1916) was a British painter and illustrator. It is known that he worked in London, England starting in 1873 and that he stayed in the city until at least 1890. Britten’s work ranged in style from to traditional Victorian to Pre-Raphaelite, and his artistic medium ranged from paintings to book illustrations. His paintings have mostly been praised by critics with his illustrations having been treated as either neutral or favourable by reviewers.

- Nikosthenes was a potter of Greek black- and red-figure pottery in the time window 550-510 BC. He signed as the potter on over 120 black-figure vases, but only 9 red-figure. Most of his vases were painted by someone else, called Painter N (for Nikosthenes). Beazley considers the painting “slovenly and dissolute;” that is, not of high quality. In addition, he is thought to have worked with the painters Anakles, Oltos, Lydos and Epiktetos. Six’s technique is believed to have been invented in Nikosthenes’ workshop, possibly by Nikosthenes himself, around 530 BC. He is considered transitional between black-figure and red-figure pottery.

THE READING WORKSHOP

PHASE 1: ENTERING THE EBOOK: UNIVERSE, ATMOSPHERE AND HYPOTHESES

Activity: Guess Where and When- Creating the storyline of the adventure of Odysseus in the island of Lotus-Eaters

Activity to enter the ebook world

Material

- Printed pictures of the e-book;

- World map.

Procedure

Before the session:

Print images from the e-book so you could help the participants fill in the storyline of Odysseus in the island of Lotus-Eaters.

During the session:

- Divide the participants into small groups of 4-5 persons. Distribute the images and the storyline to be filled in by each group and the world map, related to the location and time of the story.

- Once all participants have seen them, give them some clues about the time and place of the story and ask them to put the images in line and thus to create the storyline of the episode of Odysseus in the island of Lotus-Eaters. Propose them to discuss with their partners and share their hypotheses.

- After they share their thoughts in groups, invite them to present the storyline of the Odysseus in the island of Lotus-Eaters as a team to the rest of the groups/teams.

Alternative

It is possible to focus more on “Where and What” of the adventure of Odyssey in the island of Lotus-Eaters. You can ask participants to imagine and draw the island of Lotus-Eaters and the activities of the islanders. They can work individually or in small groups. Ask them to present what they have drown. Encourage everybody to participate in, event the hesitant ones.

Questions as facilitators:

- Can you show in the map where you think the island of the Lotus-Eaters was?

- Can you draw the shape of the island?

- What the Lotus-Eaters were doing during the daily life?

- Can you draw what these islanders were eating?

- Can you draw the Lotus flower?

PHASE 2: DIVING INTO THE EBOOK

Activity 1: Let’s meet the characters!

Preparation activity for global understanding

Material

- Printed images of the characters

- Labels for their names

Procedure

Before the session:

- The cut-out images of the characters

- The labels of the names of these characters, written in a suitable size and font.

During the session:

This first activity is proposed before reading.

- Divide the participants into subgroups. Distribute to each sub-group the illustrations of the characters. Give them some time to look at them and make their first assumptions.

- Then give them the name tags and ask them to match them with the correct image. Invite the sub-groups to associate them with the faces, then to imagine the links between them, their jobs, etc. Adapt the instructions according to the group. For example, ask them to imagine more complex elements to explain to the groups with advanced oral skills. Names will be read out to groups of people who read little or not at all, and then possibly recognised by matching the first letter of the name with its initial letter.

- When they have matched all the labels with an illustration, invite them to present them.

Alternative

You can use pictures indicated and narrating the whole story of Odysseus. You can then ask participants to answer you the following questions or via a drawing or using some of the words of the ebook (you can print some words of the ebook written in a suitable size and font and give them to the participants to use them):

- Who is Odysseus?

- Where does Odysseus come from?

- Who are Telemachus and Penelope?

- Why does Odysseus leave Itaca?

- Where did Odysseus go?

- How can you describe/imagine Odysseus?

- For how long Odysseus was away from his home?

Activity 2: Key elements

Global understanding activity

Material

- Few pictures from the e-book

- Colour pencils

- Scissors

- Blank sheets of paper

- Glue or tape

Procedure

Before the session:

Select a few images from the ebook showing the time and place(s). Prepare as many sets of images as there will be sub-groups.

The workshop:

This second activity is carried out after a first individual reading of the ebook.

- Remind to them that the points to be checked are the following: where and when does the action take place? Who are the actors and actresses in the story, what family, friends and other ties unite them?

- Go into the groups to help, if necessary, the participants to formulate their thoughts.

- Invite everyone to read and listen, and then to reflect individually, before sharing the results of their survey.

- Distribute the material (sheets, pencils, glue …), and relevant pictures from the e-book. Ask the sub-groups to make a collage or a mind map presenting the key elements discovered. Explain to them what a collage and a mind map are. Depending on the skills of the audience, it could be pictures, drawings, words.

- Put the collage or the mind map on the wall/space in the room dedicated to the ‘Odyssey’ebook.

Activity 3: Major Events

Fine tuning activity

Material

- Pictures of the ebook in one copy

- Paragraphs, sentences or words from the ebook (depending on reading level)

- A timeline of the episode (provide them with a short and easyreading template plenty of images)

Procedure

The workshop:

This third activity is carried out after a second individual reading.

- Display the images of the ebook in their order of appearance. Next to them, display text excerpts.

- Introduce the activity: individually, reread the ebook taking your time to better understand the story. Then choose 2-3 key images from the story. Indicate that it is also possible and interesting to search for the corresponding text extracts to associate with the image. It will then be necessary to accompany groups of non- or small readers.

- Ask the participants to discuss their choice in pairs.

- A few volunteers show the selected images (and possibly text extracts) and explain themselves.

- Facilitate a discussion on the chronology of the story (give them a short timeline), the events that mark it out and what seems most important. This is an opportunity to discuss what is not understood or what seems strange, and thus to explain certain socio-cultural aspects of the period and compare them with the current period in different countries.

Activity 4: Storyline flashcards

Fine tuning activity

Material

- Printed templates of flashcards

- Printed questions related with the storyline

- The infographic

- Pencils

- Glue

- Blank sheets of paper for notes

Procedure

Before the session:

Select a few images from the ebook showing the time and place(s). Prepare as many sets of images as there will be sub-

- Give the templates of the flashcards and 5 questions to each group.

- Each group will have to create 5 flashcards.

The workshop:

This fourth activity is done after a third individual reading.

- Form 3 groups.

- Ask each group to reread the e-book all together.

- Provide all groups with a short summary of the story.

- Give them some time to observe the templates of the flashcards, the questions and the answers.

- Explain to them what is a flashcard.

- Tell them to try to write 5 questions; each related to a scene of the story. Give them some clues as regards the structure of the questions.

- Ask them to answer the written questions by using words from the e-book.

- Ask each group to present their flashcards.

- Once all groups have finished their presentations, invite them to comment on the other groups’ flashcards. Give them some time to discuss and verify if the flashcards provide them with the correct answers.

PHASE 3: THE CREATIVE STAGE

Activity: Forgetting the past

Activity to enhance the reading experience

Procedure

Before the workshop:

Create a calm atmosphere with some soft background music. Alternatively, ask the participants for silence.

During the workshop:

- Ask participants to think about the times they wanted to forget something related to their past (e.g. an experience, an event). Does the same stand for persons? If so why?

- Ask participants to take a role card out of the hat. Tell them to keep it to themselves and not to show it to anyone else. Take some time and explain to them their roles (the roles are: Odyssey; Penelope; Telemachus; man of Odyssey; Lotus-eater).

- Invite them to sit down (preferably on the floor) and take some time to reflect on that.

- Now ask people to remain absolutely silent as they line up beside each other (like on a starting line).

- Tell the participants that you are going to read out a list of situations or events. Every time that they can answer “yes” to the statement, they should take a step forward. Otherwise, they should stay where they are and not move.

- Read out the situations one at a time. Pause for a while between each statement to allow people time to step forward and to look around to take note of their positions relative to each other.

- At the end invite everyone to take note of their final positions. Then give them a couple of minutes to come out of role before debriefing in plenary.

Example of statements:

- I forgot what I ate yesterday.

- I forgot my friends.

- I forgot to be loyal.

- I forgot my homeland.

- I forgot my wife/husband/son.

- I forgot my childhood.

- I forgot to take care of my companions/family.

Debriefing and evaluation:

Start by asking participants about what happened and how they feel about the activity, and then go on to talk about the issues raised and what they learnt.

- How did people feel stepping forward – or not?

- For those who stepped forward often, at what point did they begin to notice that others were not moving as fast as they were?

- Can people guess each other’s roles? (Let people reveal their roles during this part of the discussion)

- How easy or difficult was it to play the different roles? How did they imagine what the person they were playing was like?