Aim: To support educators in understanding people with disabilities’ world. It’s important that educators and teachers become aware of the importance of language and of the terms nowadays used when talking of disability, the “disability etiquette” and the main document for the diagnosis of disability.

To have in mind some good example of how “disability” does not mean “limit” is useful in order to motivate all the students.

Key words: disability; ability; etiquette; language.

Prior knowledge: Teachers that want to get close to all their students, don’t have to already possess particular knowledges or skills, of course the more they already know about didactic and disability, the better it is. The most important requirements in any case are curiosity and open-mindedness.

This sheet wants to be a support for the daily approach with students in order to go beyond the labels society usually gives.

Introductory readings about the topic will be provided in order to allow learners to get in and go deeper also in an autonomous way.

Main Part

So far as language both shapes and reflects social reality, the words we use about disability have a significant impact on the way it is perceived. The words we use should never be offensive because the discriminatory language, for example, labels such as “cripple”, “mongoloid”, “retarded”, is both a symptom of, and a contributor to, the negative attitudes and the unequal social status of people with a disability.

Labels doesn’t describe the real attitudes and capacities of the person: people are not their disabilities, the “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health” (ICF) is a classification of health and health-related domains that doesn’t focus only on the person, but on the environments too. The environment can be a facilitator in one person activities, but can also be a barrier and can not allow some abilities. ICF is recognized by the World Health Organization as a good support in order to outline the best educative path for people with disabilities to overcome the barriers they can meet.

History shows us that disability is only a characteristic of the person and not a barrier:

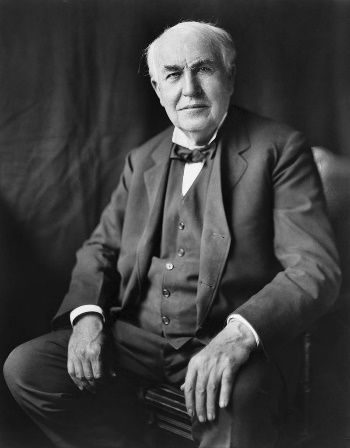

- Thomas Edison: Inventor and businessman, recognized as one of America’s greatest inventor. He is the father of many devices we nowadays daily use, such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures.

Did you know he was deaf?

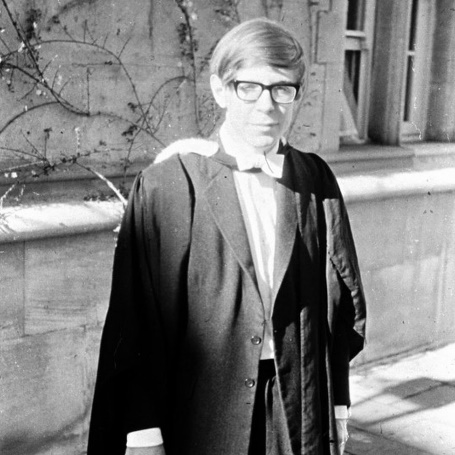

- Stephen Hawking: Theoretical physicist, astrophysicist, cosmologist and eminent scientist. He received a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at the age of twenty-one.

- Alex Zanardi: Italian professional racing driver in Formula One, he had a terrible accident in 2001 that causes the lower limb amputation. He started a carrier in the handcycling and became world champion at the Paralympic games.

People with disabilities are not victims or braver than people without disabilities, first of all they are people, that’s why patronising or sentimental words are not necessary.

- Put the persons first, their disability – impairment – is only secondary. Their disability does not tell you who they are, what they are like or how they feel. You must get to know them as a person to find these things out. Say “person with a disability” rather than “disabled person”.

- Avoid using outdated terms such as “handicapped”, “invalid” or “crippled”. The terms ‘able-bodied’, ‘physically challenged’, ‘differently abled’ and ‘sufferer’ are also strongly discouraged. Make up the difference between “disability” and “handicap”: when someone loses a leg in an accident, this disabling condition will remain throughout the person’s lifetime. It may be a handicap in, e.g. walking, riding a bicycle or working as a waitress, but not while playing card games, cooking a meal or working as a computer operator.

- When we speak of persons with a disability, we do not refer to the disability as a disease. Disease describes a contagious condition. Most persons with disabilities are as healthy as anybody else.

- Avoid saying ‘normal’ to describe people without disabilities, which implies that people with disabilities are not normal.

- Address a person with a disability directly, not through a third person.

- It is acceptable to use idiomatic expressions when talking about people with disabilities. For example, “It was good to see you” and “see you later” to a person with vision impairment – they use these expressions themselves all the time!

Task/Exercise or Formative Assessment

We propose you to fill a table with your strengths and weaknesses and reflect on them: do you think weaknesses can turn into strengths? What’s the positive aspect of your weaknesses? What you can do that others can’t and thanks which you are considered an important part of the group?

Such reflections can be “moved” on everyone, people with disabilities too: what do I see, the person or only the disability?

Desirable outcome

At the end of this practice sheet, the educator should be aware that how we speak creates the world that is around us. Give people labels is not useful in their personal grow and means nothing since everyone can do everything. What is desirable is to always respect differences and look at the abilities, what is positive in the person, not the disabilities.

References / Additional Resources

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

- “Understand your abilities and disabilities. Play to your strengths.”

- “Focus on Ability Interacting with people with disabilities” by NASA Johnson Space Center, Office of Equal Opportunity and Diversity

- “Different Ability Versus Disability: Why Language Matters” by Eleanore Belanger, Arizona State University

- “Thomas Edison’s Greatest Invention” by Derek Thompson

45 minutes | For educators

45 minutes | For educators